RECENT POSTS

Chef Pipelines

Aug 2, 2018

Safely Publishing and Promoting your Organization’s Chef Policy

Overview

There is no time like the present to review the automation that builds, tests, publishes and promotes your Chef policy safely and predictably in your place of work. If this is not something that you have mostly automated, or perhaps haven’t yet started working on, then please continue reading! On the other hand, if you already have automation in place, as I mentioned, there could still be room for kaizen. In the rest of this article I will refer to this automation as a Pipeline. Ultimately, you should have many Pipelines with distinct responsibilities and a model that scales for all your Chef Policy, where adding more Pipelines is a simple undertaking.

First, let’s define what I mean by Chef Policy. Typically you might think of Chef Policy as just cookbooks or policyfiles. There are many examples of pipelines that check and publish cookbooks. However, in this article I am going to take a more comprehensive approach and define Policy as ALL objects that coalesce together when nodes converge.

Let’s dive into how to do this. But before we can do this, we shall enumerate our Chef Policy as the following objects:

- cookbooks (broken out into dedicated repos, with a project-wide Berksfile at the root of the

chef-repo) - roles

- data bags

- environments

- policyfiles

- nodes

All these items represent the most important objects in a chef-repo that should be kept up to date in version control.

With the exception of cookbooks and policyfiles, the remainder are not versioned. The object as it

exists on the Chef Server is the source of truth. Transferring ownership of those objects to

source control is the key to successfully implementing Pipelines.

Note Somewhat outside the scope of Chef Policy, yet worth mentioning, are InSpec Compliance Profiles. These also benefit greatly from being pushed through a Pipeline.

Pipeline

Generally speaking a Pipeline is anything that acts on a source control code commit or merge (PR)

request and performs automated tests and promotion of that code change. With regards to Chef

Policy, the pipeline’s job is to replace the manual process that was typically performed by knife

commands.

Important Pipeline Principles

- Infrastructure as Code everything about your company that is electronic and moves should be treated as code and should be in source control, then driving a Pipeline to deliver the content.

- Manual testing and promotion of changes will inevitably result in fails - automate all of this

- Manage the code being tested/promoted alongside the automation policy (such as a

.travis.ymlor Jenkinsfile) in the same repo. Do not decouple the two. - Restrict

knifewrite access to a very limited number of Chef admins and the Pipeline user. Everyone else gets read-only or no access. Use a tool like Chef Automate for visibility into changes. Limit read-only via knife-acl - Your Chef Pipelines should adhere to the well established patterns of continuous delivery. Just because you are continually publishing the cookbooks does not mean they are going to be consumed in Production immediately. See the “Promoting” section below for more on how to safely accomplish that.

Pipeline Toolbag

As an automation practitioner, your toolbag is ever changing and being optimized. With that in mind, here are a sample of tools that can help that you should at least be aware of in no particular order. Best of all, everything is already included in the ChefDK:

- ChefDK

- chef-client

- chef-zero

- knife cmds (inspect, upload, spork, acl, vault)

- berks (berkshelf)

- test kitchen

- foodcritic

- chefspec

- chefstyle

- inspec

- rake

- rubocop

As you can see, the DK is a gold mine of important tools, and easy to install.

Pipeline Stages

Conceptually, you can break down the stages of the pipeline into two buckets:

- Test

- Promote

Chef Automate Workflow has very nice build out of these two general stages into six

Generally speaking, the pipeline will do these things with the artifact during stages:

- Test

- lint (ex. cookstyle, rubocop, foodcritic)

- unit (ex. chefspec)

- integration/smoke (ex. test-kitchen, inspec)

- Promote

- upload (ex. knife upload .., berks upload, knife supermarket share)

One great example of how simple but effective the Test stage can be is Chef’s standardized

.travis.yml file that exists for all community cookbooks: see it here in full

Here are the most important parts:

before_script:

- sudo iptables -L DOCKER || ( echo "DOCKER iptables chain missing" ; sudo iptables -N DOCKER )

- eval "$(chef shell-init bash)"

- chef --version

- cookstyle --version

- foodcritic --version

script: KITCHEN_LOCAL_YAML=kitchen.dokken.yml kitchen verify ${INSTANCE}

matrix:

include:

- script:

- chef exec delivery local all

env: UNIT_AND_LINT=1

For integration testing, some approaches that can be used very effectively are:

- Test Kitchen This is a great example

- Maintaining an integration environment that mirrors production and smoke test it after converging

- If running in a Chef Server less fashion, provision a canary node, tar’ing up the chef-repo to the node, and running chef-zero with the chef-repo artifact.

- Terraform with inspec is a nice pattern for smoke testing

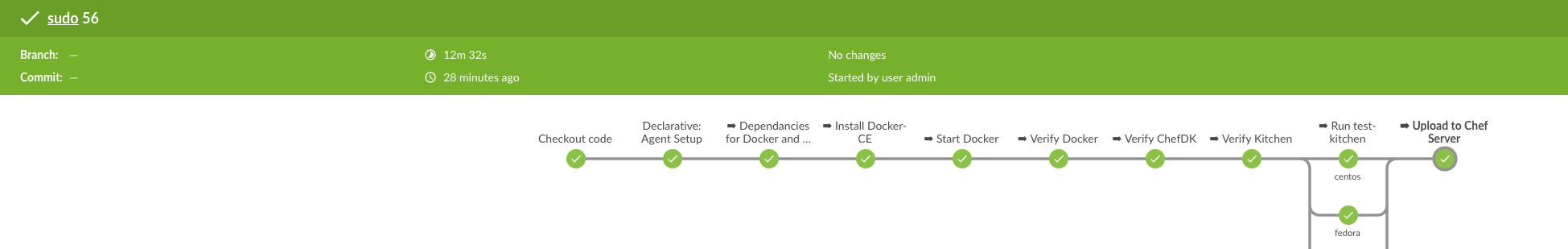

Chef Policy Upload

After all linting, syntax and other checks are completed successfully it’s safe to upload the Policy

to a Chef Server. In this article I’ll mention doing so with Jenkins. However nothing precludes you

from using another Pipeline toolset. Jenkins 2.0 introduces a Pipeline driven by a Jenkinsfile,

making it very simple to drop into every repo, managing the code and automation together.

Again, the actual implementation of uploading Policy is almost ridiculously simple. It just boils down

to berks upload .. and knife upload ... Lamont Lucas has a great example in a Jenkinsfile.

stage('Upload') {

when { branch 'master' }

steps {

sh 'echo uploading'

withCredentials([file(credentialsId: 'chefadmin.pem', variable: 'CHEFPEM')]) {

sh '''

berks install && berks upload

knife upload /roles /data_bags /environments --chef-repo-path .

'''

}

}

}

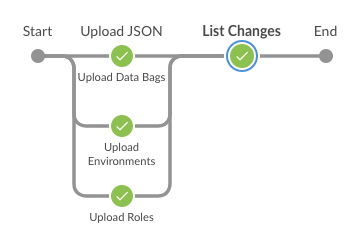

Visually, in Jenkins Blue Ocean there is an elegant simplicity.

Another Jenkinsfile with a different approach, by JJ Asghar, this time using Docker.

Cookbook Promotion Across Environments

Finally, one of the most important concepts to cover is how to promote your cookbook policy in a safe and scalable fashion.

Creating Chef Environments to match your Infrastructure Environments allows you to speak the same language with other groups within your organization and lessens the overhead of managing constraints by keeping the number of Chef Environments to a bare minimum. This is a great pattern for something like a Jenkins Chef cookbook pipeline to utilize.

A typical organization might have Infrastructure Environments like:

- Dev

- Staging

- Prod

Note: Application Environments are also a proven pattern, although automation is key to managing these as it won’t scale manually. An example Application Chef Environment: “Sales-Staging”

A Chef Environment can be represented via json like this:

{

"name": "Staging",

"description": "This is the Staging pre-production environment.",

"cookbook_versions": {

"acme_finance_web": "= 1.0.2",

"acme_marketing_web": "= 0.1.2",

"acme_sales_pos": "= 0.1.1"

},

"json_class": "Chef::Environment",

"chef_type": "environment",

"default_attributes": {

},

"override_attributes": {

"ldap_server": "ldap-staging.acme.com"

}

}

As you can see above Chef allows you to constrain cookbook versions in an Environment. Any nodes in that Environment will only be able to run these cookbook versions.

For more on Versioning see: http://semver.org

Opt-in Will Scale

It may be tempting to use the Chef Environment to constrain every cookbook that exists. However, this will lead to version dependency nightmares.

For example, if Team A has Cookbook “team_a”, and Team B has Cookbook “team_b” and both of them depend upon a shared Library Cookbook: “library_z” which happens to be constrained in an Environment with an equality constraint; any new Release of “library_z” will need to be coordinated across both Team A and Team B. This strategy will simply not scale.

A much easier approach to managing this is to allow for a “Opt-in” style where Team A and Team B are able to move to newer versions of “library_z” only when they are ready and after thorough testing. The latest version of “library_z” cookbook exists in all environments because there are no Chef Environment version constraints for it. The “library_z” version constraints are encapsulated in the consuming cookbook’s metadata.rb.

This requires an approach of only managing version constraints for individual Team cookbooks in Chef Environments by carving out a uniquely named “Role” for them, version Pinning that “Role Cookbook” in the Environment and allowing the teams to manage all dependencies within their Role Cookbook. This allows Teams more autonomy to move at varying speeds promoting artifacts across Chef Environments without fear of a surprise unresolvable dependency constraint imposed by another Team or Group when they promote into a new Environment. It significantly lessons the burdens on the Chef Administrators / DevOps Champions who then do not have to “police” cookbook promotion, allowing the whole Organization to begin autonomously developing with Chef.

An organization’s pipeline should be able to “promote” these Role Cookbooks from one environment to the next after each dependent component passes comprehensive automated unit, integration, regression, smoke and acceptance/functional tests of the whole stack. Promotion entails the Pipeline adding or updating the Chef Environment constraint for the Role Cookbooks in an automated fashion. Perhaps using a tool like Knife Spork: https://github.com/jonlives/knife-spork. Chef Automate’s Workflow component handles this automagically for you.

Individual users should not have the permissions to manipulate Chef Environments directly. Rather, changes should be initiated through version control and pushed to the Chef Server via automation in the Pipeline. The Pipeline operates with a service account and is likely one of the few necessary accounts needed to be created on the Chef Server.

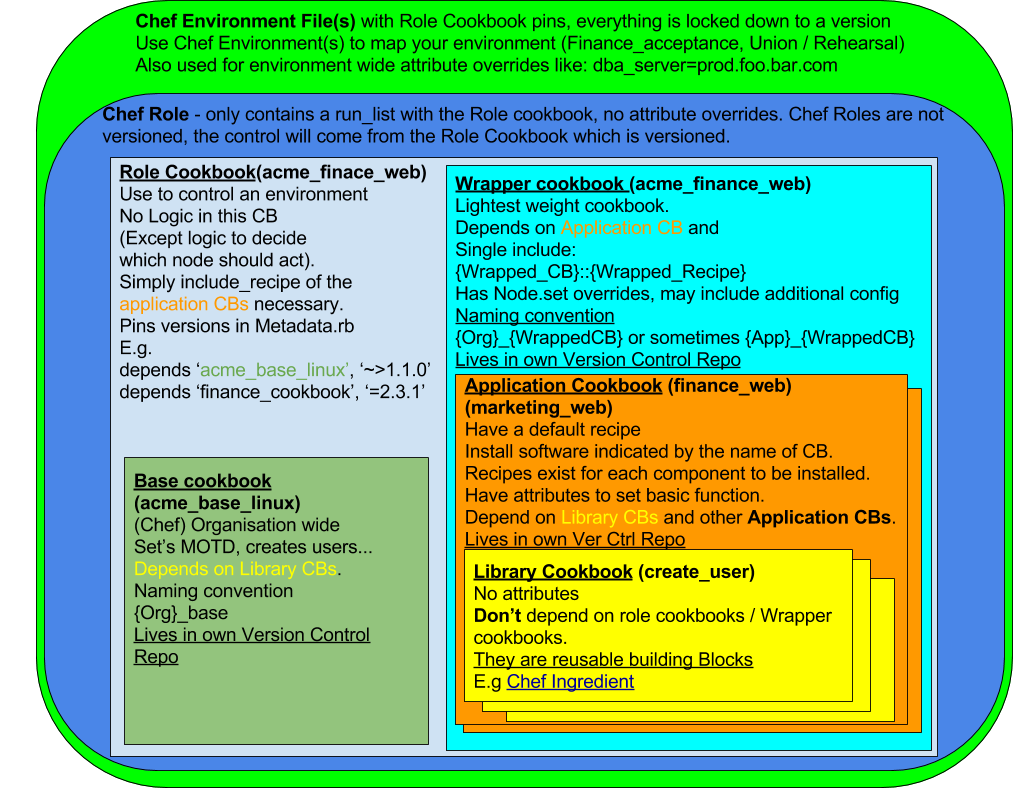

To implement this, it is important to understand the Cookbook types.

Cookbook Archetypes

Let’s look at the Cookbook types that fundamentally enable this to happen safely and with ease.

The Library Cookbook

Most basic build block. These are meant to be reusable and depended upon by other Cookbooks to provide functionality.

Library Cookbooks provide things like:

- Adding Custom Resources that abstract common functionality

- Including Libraries that add Ruby modules/classes for any depending cookbooks

Generally these do not have attributes since there is nothing to configure and often do not include any recipes.

Library cookbooks may depend on other library cookbooks or application cookbooks. They never depend on a Role Cookbook and they never depend on a Wrapper cookbook.

An example: https://github.com/chef-cookbooks/chef-ingredient

The Application Cookbook

These cookbooks are a level above Library cookbooks. They always contain at least one recipe (the default recipe) to install a particular piece of software sharing the same name as the cookbook. If the application the cookbook manages contains multiple components then each one is broken up into it’s own recipe and the recipe is named after the component it will install. Things are broken up in this way so you could install various components spread across a number of nodes within an environment.

These cookbooks almost always contain a set of attributes which act as the runtime configuration for the cookbook. These attributes can do something like setting a port number or even describing the desired state of a service.

Attribute precedence level Application cookbooks should always just be default.

These cookbooks are always named after the application they manage.

Application cookbooks may depend on Library Cookbooks and other Application Cookbooks. They never depend on Role Cookbooks. They never depend on a Wrapper or Base Cookbook unless they are intended to be internal to your organization and will never be distributed to the Chef Community Site.

Every Application cookbook should live in it’s own version control repository.

The Wrapper Cookbook

This is the lightest Cookbook out of all the known Cookbook patterns. It does a very simple job of depending on an Application Cookbook and then exposing a recipe for each recipe found in the Application Cookbook that it is wrapping. In these recipes a single call to include_recipe “{wrapped_cookbook}::{wrapped-recipe}” will be found along with a number of node.normal[] or node.override[] functions which override the default attribute values of the wrapped Cookbook. See Chef Attributes.

Wrapper cookbooks depend on Application Cookbooks only. They do not depend on other Wrapper Cookbooks, Library Cookbooks, or Role Cookbooks.

These cookbooks follow the naming convention {organization}_{wrapped_cookbook}

or even sometimes {application}_{wrapped_cookbook}.

Every Wrapper cookbook should live in it’s own version control repository.

The Base Cookbook

Each organization should have one of these. This cookbook does the job of setting the MOTD on your machines or creating users and setting them up with zsh instead of bash. This cookbook can become a sort of “junk drawer” so you should be careful when adding to it. Things should only be added here when it doesn’t make sense to place them in another spot.

This is another cookbook pattern that you don’t see out in the wild because it’s specific to your organization and shouldn’t be shared with anyone else.

Base Cookbooks may depend on Library Cookbooks, Application Cookbooks, or Wrapper Cookbooks. They never depend on an Role Cookbook.

These cookbooks follow the naming convention {organization}_base. Every Base cookbook should live in it’s own version control repository.

Example metatdata.rb of a Base Cookbook:

name 'acme_base_linux'

maintainer 'Acme Co., Inc'

maintainer_email 'devops@acme.com'

license '# Copyright (c) 2016 Acme Co., Inc, All Rights Reserved.'

description 'Installs/Configures acme_base_linux'

long_description IO.read(File.join(File.dirname(__FILE__), 'README.md'))

version '2.0.4'

source_url 'https://github.com/acme/acme_base_linux'

issues_url 'https://github.com/acme/acme_base_linux/issues'

depends 'chef-client', '= 4.3.3'

depends 'chef-handler-profiler', '= 1.0.1'

depends 'chef-splunk', '= 1.8.0'

depends 'datadog', '= 2.1.0'

depends 'datadog_support', '= 2.6.0'

depends 'firewall', '= 2.3.0'

depends 'ntp', '= 1.7.0'

depends 'openssh', '= 1.5.2'

depends 'opsmatic', '= 0.1.26'

depends 'opsmatic_support', '= 0.1.7'

depends 'selinux', '= 0.8.1'

depends 'splunk_support', '= 0.6.0'

depends 'sysctl', '= 0.6.4'

depends 'sysctl_support', '= 1.2.0'

depends 'tmpwatch', '= 2.0.0'

depends 'yum-gd', '= 0.7.1'

depends 'os-hardening', '= 1.2.1'

Example Default Recipe of a Base Cookbook:

raise if node['platform'] == 'windows'

include_recipe 'yum-gd' if node['platform_family'] == 'rhel'

include_recipe 'chef-handler-profiler'

include_recipe 'chef-client::config'

include_recipe 'chef-client::service' if node['chef_client']['service']['enabled'] == true

include_recipe 'chef-client::delete_validation'

if node['acme-selinux']['enabled'] == false

include_recipe 'selinux::permissive'

else

include_recipe 'selinux::enforcing'

end

...

The Role Cookbook

This is the piece that ties the release process of your development cycle together and allows you to release software that is easy to install and to configure.

A Role Cookbook should not contain any logic of it’s own - it should simply include_recipe on the Application Cookbooks necessary. One exception is that it can include logic about which nodes should get which services, and any orchestration that has to happen. The version of the Role Cookbook will be pinned in the Chef Environment.

Again, the Role Cookbook has metadata.rb depends entries (with version pins) for each cookbook that you will want to converge on the node and will have include_recipes entries in the default recipe for each dependent recipe component required.

Be sure to include the “base” cookbook if you have one.

Example metatdata.rb of a Role Cookbook:

name 'acme_finance_web'

maintainer 'Acme Finance'

maintainer_email 'finance-devs@acme.com'

license 'All rights reserved'

description 'Role cookbook for finance_web application'

long_description IO.read(File.join(File.dirname(__FILE__), 'README.md'))

version '1.0.2'

depends 'acme_base_linux', '~> 1.1.0'

depends 'finance_cookbook', '= 2.3.1'

Example Default Recipe of the Role Cookbook:

include_recipe 'acme_base_linux'

include_recipe 'finance_application::keys'

include_recipe 'finance_application::web'

Sometimes a Chef Role may be created to house the Role Cookbook. However, it should NOT contain any attribute overrides and anything other than one run_list entry: the Role Cookbook. This is important because Chef Roles are not versioned. Changing a Chef Role immediately affects ALL nodes across all environments that have the Role applied. Instead, allow the Role Cookbook to version the run_list and dependency pins and perhaps override attributes. This allows for safely promoting your changes, one environment at a time.

Example Chef Role:

{

"name": "acme_finance_web",

"description": "Installs and configures all components for a Finance Web server.",

"json_class": "Chef::Role",

"default_attributes": {

},

"override_attributes": {

},

"chef_type": "role",

"run_list": [

"recipe[acme_finance_web]"

],

"env_run_lists": {

}

}

Finally, the Chef Environment Files with Role Cookbook version pins:

This Development Environment has no constraints - latest versions get used.

{

"name": "Dev",

"description": "This is the Dev. The latest and greatest versions.",

"cookbook_versions": {

},

"json_class": "Chef::Environment",

"chef_type": "environment",

"default_attributes": {

},

"override_attributes": {

}

}

Staging Environment with equality version constraints.

{

"name": "Staging",

"description": "This is the Staging pre-production environment.",

"cookbook_versions": {

"acme_finance_web": "= 1.4.1",

"acme_marketing_web": "= 1.1.8",

"acme_sales_pos": "= 0.10.9"

},

"json_class": "Chef::Environment",

"chef_type": "environment",

"default_attributes": {

},

"override_attributes": {

}

}

Production Environment with equality version constraints.

{

"name": "Prod",

"description": "This is the Production environment.",

"cookbook_versions": {

"acme_finance_web": "= 1.0.1",

"acme_marketing_web": "= 0.1.0",

"acme_sales_pos": "= 0.1.0"

},

"json_class": "Chef::Environment",

"chef_type": "environment",

"default_attributes": {

},

"override_attributes": {

}

}

Notes: In other articles and discussion circles you may sometimes hear the words “Role Cookbooks” and “Environment Cookbooks” used interchangeably.

Visual Representation of this Environment Pattern

Additional Resources

- Lamont Lucas ChefConf 2018 Session

- Noah Kantrowitz thoughts on docker Jenkins

- Michael Hedgpeth has a great Jenkinsfile

- TYPO3 real world Jenkins pipeline libraries

- The Environment cookbook pattern

- Roles aren’t evil

- Many great Chef Recommendations

- Chef Evaluation made Easy

- Workflow Global Build Cookbooks

- JJ Asghar’s Docker Jenkinsfile